by Jerseyman ©2010

Researched and written at the request of a true friend to New Jersey history.

Beginning in the early nineteenth century, a variety of gentlemen societies established clubhouses along the New Jersey side of the Delaware River. Founded primarily by Philadelphians, these organizations normally formed around sporting activities such as fishing and gunning and their origins can be traced to the Colony in Schuylkill Fishing Company, which changed its name to State in Schuylkill Fishing Company after the colonies won the American War for Independence (Smith 1986:106). Writing about one these clubs—the Tammany Pea Shore Fishing Company—Isaac Mickle noted, “…the club had its origin in that old English social feeling which so strongly marked the generation of our grandfathers” (Mickle 1845:46). The Colony in Schuylkill Fishing Company, founded in 1732, is the earliest gentlemen’s club established in the English New World. Other similar associations along the New Jersey shore that existed during the nineteenth century and into the twentieth century included the Beideman Club, the Sparks Club, the Mozart Club, the Mohican Club, and the Riverton Gun Club.

On the shores of the Delaware at Gloucestertown (now Gloucester City), Quaker City residents sought a variety of entertainment venues down through the years. Anglican pastor Nathaniel Evans, who held services in Gloucestertown during the mid-1760s, wrote a poem titled, “The Morning Invitation, to Two Young Ladies at the Gloucester Spring.” Evans died prematurely at age 26 and William Smith, a friend and admirer of Evans, published a collection of his poems, including the one just referenced, posthumously in 1772 by the subscription method (Evans 1772). Another early entertainment offered to an elite membership was the Gloucester Fox-Hunting Club. Belonging to this hunt association provided a certain cachet to its members, many of whom constituted the social elite of Philadelphia. The club operated between 1766 and 1818 before disbanding (Milnor 1889:405-429). Hunts usually ended at the “Death of the Fox” Tavern, a building that still stands in East Greenwich Township, Gloucester County, next to the railroad. Twenty years after foxhunting ceased, another group of Philadelphians, led by Izaak Walton devotee and sail-maker Jesse Williamson, formed a fishing club, which met below Gloucester Point. The broad, sloping Gloucester river shore had hosted fisheries since the early eighteenth century. Names associated with the fisheries there include Harrison, Ellis, Hugg, Shivers, and Clark. Beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, shad hauls at Gloucester became legendary, particularly once the hotels offered a delicacy known as “Planked Shad” (Prowell 1886:604-606).

Prowell suggests that Williamson and his colleagues may have organized their club in 1828, but more contemporaneous evidence presented below appears to refute that earlier date, which earlier date Prowell provides with uncertainty. Initially, the members referred to their society as the Fish-House Company or the Williamson Fishing Club, as an homage to Jesse and his abilities “…in handling the rod and frying-pan” (Prowell 1886:604). The members, “…during the summer months, met semi-weekly under the large sycamore trees that once lined the shore of the Delaware, from Newton Creek to Timber Creek” (ibid.).

In October 1839, club members John B. Rice, William J. Young, and William F. Hughes, all Philadelphia residents, leased some of the Clark fishery lands from Joseph Howell and William Hugg. The lease agreement covered the ensuing nine years at a cost of $40 per annum. The club also received permission to construct an ice house and a clubhouse, which they did south of Gloucester Point along the beach below Charles Street (Llewellyn 1976:127). At some point subsequent to finishing the clubhouse, the membership restyled their organization “The Prospect Hill Association.” The meeting and dining hall stood on “…Prospect Hill, a high bluff overlooking the mouth of Timber Creek to the south” (Prowell 1886:604). In all likelihood, this same prominence once held the seventeenth-century Dutch trading post known as Fort Nassau. Concerning Fort Nassau and this hill, Isaac Mickle notes,

The precise locality of Fort Nassau is…a matter of much debate among antiquarians. The best opinion seems to be that it was situated immediately upon the river at the southern extremity of the high land butting upon the meadows north of the mouth of Timber Creek. That position would have struck the eye of an engineer; inasmuch as a fortress thus situated could have commanded both the river and creek, while it would have been greatly secured from the attacks of the Indians by the low marshy land which surrounded it upon all sides by the north. (Mickle 1845:58, 60)

The 1842 United States Coast and Geodetic Survey chart that shows a portion of the Delaware River includes the location of the new clubhouse:

A previously unknown painting that recently came to auction depicts the clubhouse soon after its completion:

Today this painting is in a private collection. Notice the old fish cabin featured on the left side of the painting, a long-standing fixture on the South Gloucester waterfront.

The spacious new frame clubhouse featured two primary floors, along with a garret and a basement. The members met here twice a month between May and October. The officers assessed and exacted penalties for those members who failed to attend each meeting. The attendees feasted on gastronomical offerings of their own making, often, but not always limited to, a serving of fish as the main course. The first mention of the new clubhouse appeared in two Philadelphia newspapers during June 1840. The Philadelphia Inquirer noted,

Southwark Public Schools.

On Wednesday and Friday of last week, the Reed and Catharine street Female Schools took a pleasure excursion to the fish-house below Gloucester Point. They were accompanied by their teachers and some of the directors. The children all looked remarkably well, and their happy, joyous faces gave great pleasure to all who beheld the, On Friday, as we viewed them, now at the swings and now moving about in the dance, and then running like fawns along the ground, other thoughts and associations came over us, and we were children again. The greatest care and attention was paid them by their teachers, Miss Nagle, Mrs. Craycroft, Miss M. Martin and Miss Flanagan, who joined in all their festivities and were active participants in all their amusements. Too much praise cannot be bestowed upon these ladies for their active and untiring efforts to render the children happy, and they were indeed so. While upon this subject, we may say that this school was never in a better condition than it now is. The pupils are strongly attached to their teachers, which feeling they increase by devotedly performing every duty incumbent on them. Today the Female department of the Catharine street School will take a similar excursion, and on Wednesday next the male department of the Reed street School. (The Philadelphia Inquirer 22 June 1840:2)

The Philadelphia newspaper, Public Ledger, for 25 June 1840, contained a description of the male students attending the fish house at Gloucester:

SCHOOL ENTERTAINMENT.—For a week past, the new and commodious station house of the Fishing Club, in New Jersey, below Gloucester Point, near Timber Creek, has been the scene of a succession of most interesting galas, in which the chief participants were the 1200 children of the Public Schools of Southwark, with their teachers, the school directors, and a number of invited guests. On Monday last, the principal one of the district, the male school of Catharine street, numbering near 300 children, under the direction of their veteran and gentlemanly teacher, Mr. Watson, with his four lady assistant teachers, marked from the school-house to Almond street wharf, and there took the steamboat, which conveyed them to the theatre of the day’s entertainments. The appearance of the long line of men in miniature, containing, perhaps many who are destined to be the support, the pride, and the boast of their country by their ability in councils of peace or amid the rude shocks and contentions of war struck us as peculiarly pleasing. Many of them were dressed in a uniform of white pantaloons, blue roundabouts and light summer hats; all of them were neat and clean, and marched in regular order, keeping in line and step with the utmost exactness. Arrived at the Fish House, the boys divided off into parties for various amusements—bathing, swimming, diving, swinging, shouting, tumbling, climbing, running, leaping, and finally dancing, in which they had the inspiring aid of a small, but extremely good orchestra. In this the female teachers, the school directors, and all took part. Several of the ladies allowed themselves to be led out with their larger pupils, for partners, but the boys generally engaged indiscriminately in the dance, known as la grande hop, and seemed to enjoy themselves in it even more than if participators in the more regular and graceful figures of their elders. The dancing was relieved by singing. Some of the gentlemen sang, and the boys huzzaed their applause; then one of the ladies sang, and the children shouted and shouted again with delight, until they made the welkin ring—and no wonder, for the vocalists would have elicited applause from older and more critical minds. Excursions were made into the neighboring woods, and ‘’neath the shade of the greenwood tree’ the merry song, the light laugh and the cheerful shout went up, mingled with more instrumental music. At proper intervals during the day, refreshments of different kinds—hot coffee, cakes, lemonade, ice creams, &c.—were handed around. One of the young lady teachers, who appeared to be acknowledged mistress of ceremonies, wore upon her head a beautiful wreath, which had been presented to her by her scholars. Throughout the fete, the whole aim of the adults present, male and female, was devoted to rendering the children pleased and happy, in which aim they appeared to have been eminently successful. At 8 o’clock the party returned to the city. Yesterday, the male department of the Reed street school united with the Carpenter street school, and, numbering a party of more than 400, departed on the same excursion, and enjoyed themselves in much the same manner as described above. (Public Ledger 25 June 1840:2)

In an article that appeared in the 21 May 1849 edition of The Philadelphia Inquirer, is the first use of the name “Prospect Hill” in connection with the association:

Presentation of a Skiff.—A number of our most respectable citizens gave a handsome entertainment at the Prospect Hill Fishing House, below Gloucester, on Thursday last, upon the occasion of the presentation of a superb gunning skiff to Mr. John Stierley, of South Second street. The skiff is one of the prettiest things of the kind we have ever seen, and it was made by David Donaldson, of Southwark. It is called the “Sarah Ann.” This beautiful testimonial of friendship and esteem was presented to Mr. Stierley by Gen. George M. Keim, on behalf of his fellow citizens, in an exceedingly neat speech, and was received for the recipient by James Hanna, Esq. After the presentation was over, the company, numbering about eighty persons, sat down to a splendid dinner, and from the testimony of our friend, Major Copple, did ample justice to the same. On the removal of the cloth, wit, sentiment, and song occupied the time of the company until sunset, when all returned to the city, much pleased with the day’s enjoyment. (The Philadelphia Inquirer 21 May 1849:1)

A similar article appeared on the first page of The North American and United States Gazette, even date.

Based on the constitution and bylaws of the Prospect Hill Association, the membership rolls could not exceed 30 individuals. The group of men elected as officers to oversee the affairs of the association apparently served without term limits, or at least were easily reelected to office, based on a notice that appeared in a December issue of The Philadelphia Inquirer:

PROSPECT HILL ASSOCIATION.—This Association yesterday met to receive the resignation of their President, William Young, Esq., and Vice President, Louis Pelouze, Esq., two gentlemen who have long and faithfully presided over the interests of the Association. Their resignations were accepted with regret by the members, and a ballot being taken Samuel Haines, Esq., was elected President; Aaron V. Gibbes, Esq., Vice President, and William Simes, Esq., Treasurer. The Association, which is composed of Philadelphia gentlemen, have their headquarters near Gloucester, N.J., and for thirty years past have been noted for their intelligence, their skill in gunning and fishing, and their hospitality. (The Philadelphia Inquirer 8 December 1868:3)

Notice the phrase “…for thirty years past…,” which strongly supports the 1838 formation date for the fishing club. To provide its membership with clear information on its functionality, the association published its governance documents in 1856. The Historical Society of Pennsylvania holds a copy of this 12mo, 11-page pamphlet in its collections.

The association survived the national calamity known today as the Civil War. The membership continued to meet on the prescribed days and continued to use its clubhouse. During his productive years, local Philadelphia artist David Johnson Kennedy rendered the Prospect Hill Association headquarters in watercolors:

The original painting can be found in the David J. Kennedy Collection at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Individual members held their membership in high esteem and obituaries often invited the association membership to attend:

GAW.—On the 25th inst., CHARLES C. GAW. The relatives and friends of the family, also Solomon’s Lodge, No. 114, F. and A.M., and Prospect Hill Association, are respectfully invited to attend the funeral, on Saturday afternoon, at 3 o’clock, from his late residence, No. 309 Spruce street. (The Philadelphia Inquirer 26 September 1884:5)

MORONEY.—On the 20th inst., James Moroney. The relatives and friends of the family, also Hibernian Society and Prospect Hill Association, are respectfully invited to attend the funeral, on Tuesday morning at 8½ o’clock, from his late residence, 1228 Wharton street. Solemn mass of requiem at the Annunciation Church. Interment at Cathedral Cemetery. Please omit flowers. (The North American 21 July 1894:4)

With its membership growing old or dying off and with increased industrialization in Gloucester City and its attendant riverine pollution, the end for the Prospect Hill Association came in October 1897, when the members met for the its final dinner:

** The Prospect Hill Fishing Club, of Gloucester, N.J., all of whose members are Philadelphians, will give their closing dinner to-day. A number of prominent citizens have been invited and a band of music will enliven the occasion. (The Philadelphia Inquirer 5 October 1897:6)

Prowell’s history of Camden County provides a partial list of the association's membership through 1886:

Among well-known names on the list of past and present members are these,— President and Captain, E.J. Hinchen, of the Philadelphia Sunday Dispatch, who, for thirty-two years, did not miss an opening-day; James B. Stevenson, Charles W. Bender, William F. Hughes, Benjamin Franklin; Peter Glasgow, George W. Wharton, William Richardson, Peleg B. Savery, Peter Lyle, Chapman Freeman, George J. Weaver, Louis Pelouze, Mahlon Williamson, Jacob Faunce, B.J. Williams, George Bockius, Thomas F. Bradley, Joseph B. Lyndall, S. Gross Fry, Benjamin Allen, John Krider, George P. Little, Peter Lane, Samuel Collins, William Patterson, J.W. Swain, Samuel Simes, Jesse Williamson (one of the originators), and others. The membership is limited to thirty, and, as they are long-lived, the entire roll of members during the fifty-eight years of its existence contains but few over one hundred names. (Prowell 1886:604)

The clubhouse remained standing after the association ceased meeting. Its subsequent use, if any, is currently unknown. A little over five years after the last dinner in October 1897, notice of the building again appeared in the press:

CLUB HOUSE CLEANED OUT AT GLOUCESTER

Special to the Inquirer.

GLOUCESTER CITY, N.J., Dec. 15.—

George Harvey, Walter Sterling, Joseph Fitzer and Chester Sterling, boys under 20 years of age, after a hearing before Mayor Boylan to-night, were committed to the Camden county jail on the charge of robbing the Prospect Hill Club House, near the old race track. The building was ransacked from top to bottom and among the articles taken were chairs, cutlery, liquors, spoons, clocks, spigots, dishes, looking glasses, pictures, shuffleboard weights, groceries, tubs, a meat block, and in fact everything movable. The plunder was removed to a boat house along the river and was offered to a second hand dealer who became suspicious and notified the police.

The boys at the hearing, it is said, admitted taking the goods but denied breaking into the building, claiming to have found the door open. (The Philadelphia Inquirer 16 December 1902:3)

With the clubhouse becoming a convenient nuisance for local miscreants, an advertisement for selling the building appeared in March and April 1903:

Gloucester

FOR SALE—Prospect Hill Club House, situated on the Delaware River, below Gloucester, N.J.; will be sold cheap.

WILLIAM H. PRICE, 209 S. 10th st. (The Philadelphia Inquirer 25 March 1903:15)

NEW JERSEY

FOR SALE—PROSPECT HILL CLUB HOUSE, on the Delaware River below Gloucester, N.J.; easily reached by trolley; dining room will seat 60; lawn and trees around the house; kitchen arranged for planking shad. WM. H. PRICE, 209 South Tenth street. (The Philadelphia Inquirer 5 April 1903:10)

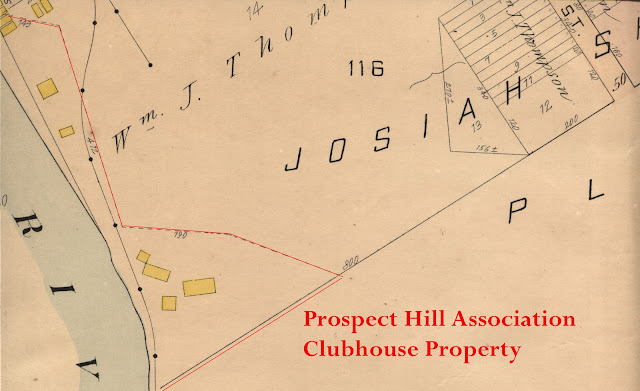

William J. Thompson, the so-called Duke of Gloucester, acquired the property as an expansion of his riverfront entertainment empire (Hopkins 1907:3). Here is a plan of the association grounds from the 1907 Hopkins atlas, showing the orientation of the buildings relative to the shoreline:

Thompson already owned the surrounding former Clark fishery and continued the tradition of fishing along the shoreline and served the shad in his hotels. When Thompson suffered financial reverses and became a bankrupt, protracted litigation ensued, with trial activity extending from April 1911 to June 1916 (The Philadelphia Inquirer 23 June 1916:3). Former Camden County Sheriff Henry J. West served as trustee in the bankruptcy proceedings and sold much of Thompson’s land holdings to satisfy the creditors, including the former Prospect Hill Association clubhouse and outbuildings. Michael Haggerty and James McNally purchased the clubhouse property and received the fishery rights as part of the transaction. McNally intended to operate a large fishing net there in 1916, but the Pennsylvania Shipbuilding Company purchased the land from Haggerty’s estate and from McNally to build a shipyard in South Gloucester. A consequence of the shipbuilding firm’s acquisition of this property was a de facto extinction of commercial shad fishing in Gloucester (Woodbury Daily Times 14 March 1916:3). Construction of the shipyard and associated buildings, along with regrading the land for such industrial pursuits brought about the demolition of the once proud Prospect Hill Association clubhouse and its existence is hardly known today.

Bibliography:

Boyce, W.M.

1842 Vicinity of Philadelphia PA. & N.J. Manuscript chart, T-165bis. United States Coast and Geodetic Survey, Washington, D.C. Original held at the National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C.

Evans, Nathaniel

1772 Poems on Several Occasions with Some Other Compositions. John Dunlap, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Hopkins, Griffith Morgan

1907 Atlas of the Vicinity of Camden, New Jersey. G.M. Hopkins and Company, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Llewellyn, Louisa W.

1976 First Settlement on the Delaware River: A History of Gloucester City, New Jersey. Gloucester City American Revolution Bicentennial Committee, Gloucester City, New Jersey.

Mickle, Isaac

1845 Reminiscences of Old Gloucester or Incidents in the History of the Counties of Gloucester, Atlantic and Camden, New Jersey. Townsend Ward, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Milnor Jr., William

1889 “Memoirs of the Gloucester Fox Hunting Club.” Published as an appendix in History of the Schuylkill Fishing Company of the State in Schuylkill, 1732-1888. By the Members of the State in Schuylkill, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Prowell, George R.

1886 The History of Camden County, New Jersey. L.J. Richards & Company, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Smith, Philip Chadwick Foster

1986 Philadelphia on the River. Philadelphia Maritime Museum, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.